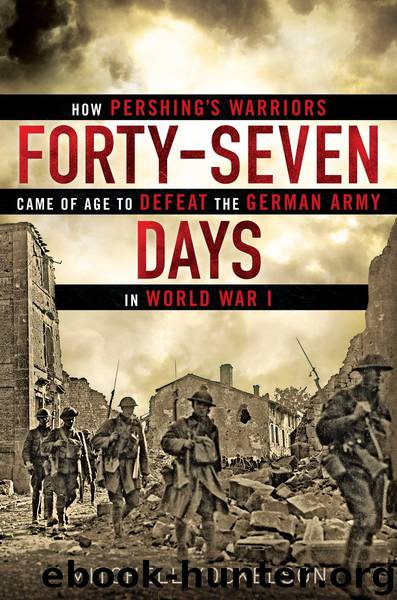

Forty-Seven Days by Mitchell Yockelson

Author:Mitchell Yockelson

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Penguin Publishing Group

Published: 2016-02-02T13:26:58+00:00

11

PROGRESS WAS MADE

By October 5, Germans under General Krug von Nidda finally retreated from Blanc Mont Ridge and formed a new line along the Aisne, but left behind were a few enemy troops who needed to be removed. To clear the ridge, a battalion of Marines jumped off behind a rolling barrage at five a.m. As the morning progressed, Major George K. Shuler’s men “hit the hill and went up the side. Not a man had dropped.”

[They] began to get into the pine trees that fringed the ridge and still there were no causalities. Slowly, carefully we followed on. Then the signal came for the lifting of the barrage, and before the last gun had ceased booming, those marines were at the entrances of the deep dugouts, their bayonets on the alert—their voices shouting for surrender.

“Hey, you Boche,” one of them shouted in German, “come on out and I’ll get you a job with the government at a dollar a day!”1

Shuler’s Marine battalion became entangled in another vicious battle that took place the next day in and around St. Étienne. At six a.m. the Americans surprised the 213th German Division, which thought it had the village secured. Fighting continued throughout the day with hand-to-hand combat on the streets. The Americans were driven beyond the south edge of town while the Germans lobbed artillery at them. By the afternoon, the Germans had enough and abandoned the village.

Blanc Mont was now completely secure, but the fighting to take the ridge had done nothing to help First Army, which remained mired on the Argonne front. Pershing’s October 5 diary entry read: “Attack resumed with little headway.” Pétain came to Souilly that day and told Black Jack over lunch, “This is something which might have happened to anyone, and there is only one course left and that is to keep on driving.”2

During the next few days the 2nd Division was slowly relieved by the 36th Division, National Guardsmen from Oklahoma and Texas under the command of Major General William R. Smith. Major General Lejeune kept his forces in place to help Smith’s green troops become acclimated. As they marched toward the front, one of Smith’s doughboys, who had yet to see combat, remarked that the Marines were “a battered, filthy, ragged crew: they did not look like soldiers. . . . Bristly growth ringed around their lips, silent mouths helped frame weary eyes that had a glare of madness in their depths.” This was “in contrast to the “fast-stepping column” of “tall, clean-cut fellows, walking rapidly toward the guns.”3

A week after Blanc Mont was taken, Billy Mitchell flew over the Champagne battlefield to make his “usual inspection and reconnaissance” in the air. Taking off from the Souilly Airdrome on October 14, Mitchell and his observer had reached an altitude of thirteen thousand feet when they passed over the chalky landscape. “I had been looking carefully for the well remembered roads to the East of Somme-Py; they no longer existed,” he wrote after the war. “I looked for the villages; they were not to be seen.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12028)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4925)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4789)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4689)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4213)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(4003)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3966)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3946)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3550)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3343)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3205)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(3189)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3133)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(3008)

Hitler's Flying Saucers: A Guide to German Flying Discs of the Second World War by Stevens Henry(2754)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2679)

The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson(2526)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2518)